Researchers find people who have lived abroad have the most successful negotiations and solutions.

University researchers, Adam Galinsky and William Maddux, conducted a series of experiments that revealed some of the benefits of pushing past the boundaries of our existing mindsets. They looked at the differences between people who have lived in two or more countries versus those who have never lived outside their country of origin.

In one of their studies, Galinsky and Maddux took 108 people and paired them up in teams of two. Each of the 54 teams was asked to negotiate the sale of a fictitious gas station. In each team, one person played the role of the buyer and one was the seller. Prior to experiment, the researchers told the buyers that they needed to purchase the gas station from their partner, but that they could only spend up to a specific amount, and no more. Sellers were told they needed to sell their gas station but they couldn’t accept anything lower than a specified amount, and no less. The buyers or sellers remained unaware that they were set-up – the maximum purchase price given to the buyers was less than the lowest amount the sellers were told they could accept. Thus, because the sale price was the single and only issue presented to the teams for negotiation, there was a huge barrier inherent in the scenario that could quickly produce a stalemate.

But the researchers also provided a potential way out. They gave people some additional information to create the possibility that the pairs might find some shared interests during their negotiation. The buyers, for example, were told in advance that they would need to hire managers to run their stations once they purchased them. And the sellers were told that they needed to acquire enough money for two-year sailboat trips, while also needing to ensure employment upon returning from these extended vacations. No one was told to use this information; participants thought it was simply additional context.

Galinsky and Maddux found that the people who had lived abroad the longest had the most successful negotiations – they reached deals where shared interests were included in the solutions. For example, sellers provided discounts below their supposed price limits in exchange for guarantees that they would receive jobs at the gas stations after returning from their sailing trips – which also satisfied the buyers’ needs for managers to run those stations. This is an interesting finding in itself, but their research didn’t stop there.

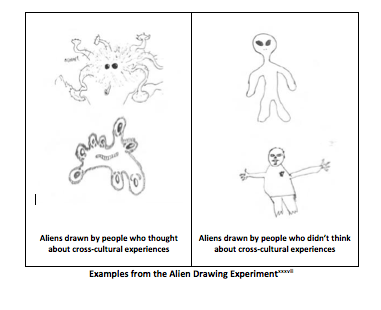

In another experiment with people who had lived abroad, Galinsky and Maddux asked their subjects to draw aliens. They found that people who had lived in another country and who were instructed to think about their experiences of adapting themselves to another culture immediately before drawing their aliens were much more creative than those who didn’t think about their cross-cultural experiences. Their drawings were more interesting, unusual, and less stereotypical than the depictions from the other subjects.

One way to better understand what could be going on with each of these studies is by taking a look at something most all of us know about: table manners. If you’re from Japan, you know that making a slurping noise when drinking soup directly out of a bowl is perfectly acceptable, whereas in the U.S. that would be considered pretty rude. If you’re from Russia, you know it’s polite to leave a little food on your plate at the end of the meal to signify that your host’s or hostess’ hospitality was abundant and plentiful; in the U.S., it’s generally considered impolite not to finish what’s on your plate. In India, people generally eat food using their right hands (because historically they do their “business” with their left), whereas in most other countries it doesn’t matter what hand you use. These are just small examples of various cultural differences that become second nature based on where we’ve lived. And the list could go on regarding the various meanings and appropriateness of behavior for everything from public displays of affection, to how you greet business colleagues, to how you shop.

You may be wondering why I’m going on about table manners and aliens and gas stations (not to mention bus drivers who aren’t really driving buses!). I’m not trying to say that people who have lived in different countries are somehow superior to those who have only lived in one place all of their lives. What I’m trying to say is this: the more open we are to new experiences and different ways of being, the better. When we’ve lived in multiple cultures or at least exposed ourselves to a variety of cultural traditions, the notions of “the right way” versus “the wrong way” begin to break down; we recognize there are alternative approaches; we see connections and patterns that we would never have seen otherwise. Our underlying mindsets shift in how we think about and approach problems and opportunities. In short: we lose rigidity. We grow more mentally limber. We find solutions that others might never imagine.

These conclusions are similar to what Galinsky and Maddux found across all their experiments – that people who understand cultural differences see more options and possibilities when faced with tough challenges. Individuals who have spent extended periods of time within different cultures are usually forced to reconcile conflicting values, norms, and behaviors. Their experience, in turn, leads them to be more flexible in their thinking, helps them make associations and connections between things that others don’t see, and gives them a natural aptitude for looking at the underlying reasons why things work the way they do.

So how does all this relate to innovation? After we have listened to ourselves and obtained a general sense of our initial focus, the next phase involves taking proactive steps to both inform and challenge our mindsets. The goal is to experience new things that trigger us to toss out old beliefs, establish new assumptions, and gain insight into additional areas that we should further exploring so we can repeat this cycle of learning. The best way to do this is to go and explore – to talk to others outside our daily grind, immerse ourselves in others’ lives, build relationships with unlikely people and partners, and do things that we wouldn’t normally do.